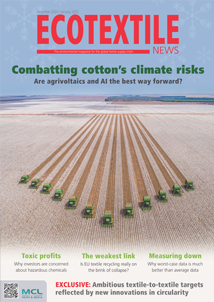

Promoters and standards setters can't be police

We need to be warily optimistic. If organisations have refused applications because developing their own offered more control and/or profit and/or centralisation, this is the wrong way to go. Monopolies are viewed as a bad thing for good reason.

Promoters can't and shouldn't police any sector due to conflicts of interest. They should however fund the solution – as should brands. They are the ones who benefit the most.

An open-source system is needed. Transparency and traceability are a big part of the solution. So is improving farmer incomes and livelihoods.

Vollaard says: “The change we want to see requires a collective effort where all actors take their responsibility, from brands and suppliers to standards and governments.”

He adds that the most recent scandal around fraud is an opportunity: “These recent discussions in regard to doubts on certification in the industry give a voice to the change-makers and puts a spotlight on the need for behavioural change,” he says.

Most people agree that more cooperation is necessary. Stripf says “only a common approach by all stakeholders in organic cotton production will solve the problem”.

But he insists that the system works because “we detected fraud and imposed a Certification Ban on 11 companies (affecting 20,000 tons of cotton, one sixth of India's total production) operating in India”. And because GOTS is developing a central database.

TE agrees: “Fraud is a complex issue that will take all of us working together to solve the problem.”

Technical solutions

Balaji A., a development manager at India-based Source Trace, which develops agri value chain management software, says the problems of fraud require physical checks on processes, but “we make tampering difficult by collecting data at every stage as well as processing the agent’s name and ID etc. so that the personnel is wary of tampering”.

Source Trace's system is based on a farmer group, each farmer having a unique ID. It captures “farm and farmer details, general ICS information” and uses a digital linked weighing scale to add data on quantity of cotton received, including date and time. Payments to farmers’ bank accounts are captured. Geolocation is used to track shipments and movements with unbroken traceability.

Balaji A. tells us it has enhanced transparency for Chetna and enabled “real-time data collection and accurate information that helps the company to monitor the production of organic cotton in an efficient manner”. He concludes: “Monitoring and evaluating improvements in social and environmental practices throughout the sustainable agriculture value chain becomes possible.”

What next?

Can progress be made? Vollaard says: “I am optimistic because I have seen what we can achieve when all actors in the chain actively engage and take responsibility.” He says the OCA is now working with nearly 80,000 farmers “close to one-third of the organic cotton farmers of India”.

But this does require opening the black boxes – for everyone to open their databases and knowledge and share. Time perhaps also for newer organisations to take the lead?

If steps are not taken now to open access to raw data, consider alternative solutions for supply chain traceability and to accept far greater industry collaboration between all stakeholders in the organic sector, then this thread will be stretched beyond breaking point, and we’ll see any remaining market confidence in organic cotton start to unravel.

And at the end of the day, it will be the impoverished farmers and their communities on the ground in developing regions that will suffer the most if this happens.

To avoid this, the organic cotton sector now needs to press the pause button, rewind and reconsider, then fast forward to a more inclusive – rather than exclusive – way of working.

Right now, it’s clear that the credibility of organic cotton in India – and by association everywhere else – is literally hanging by a thread.